Dinka and Shilluk are part of the Western Nilotic subgroup within the Nilo-Saharan language family. They are spoken primarily in South Sudan. A salient characteristic of these languages is the extent to which morphological inflection is marked through changes in vowel length, tone, and voice quality, rather than through affixes. These contrasts can be crossed with one another, as illustrated below. Comparison between columns illustrates that there are three levels of vowel length in Dinka (Andersen 1987, Remijsen and Gilley 2008): short (V), long (VV), and overlong (VVV). Comparison between rows illustrates the fact that this length contrast is crossed orthogonally with a contrast in tone – in this case Low vs. Falling.

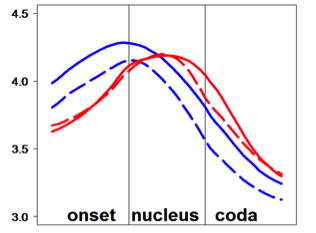

When the L tone is preceded by a High or Rising tone (as in e.g. /ǎ-lèel/), it is realized as an early- aligned falling contour. This early-aligned falling tone pattern is evidenced by the blue lines in the Figure below. Note that the blue f0 traces reach a peak near the beginning of the vowel. This f0 pattern is distinct from the late-aligned falling contour of the Fall (as in e.g. /ǎ-lêel/), illustrated by the red lines in the Figure below. Measurements of this contrast show that the early and late-aligned falling contours differ systematically in terms of the alignment of f0 peak that marks the beginning of the fall, but not with respect to other characteristics, such as the height of this f0 peak and the excursion size of the following f0 fall.

When the L tone is preceded by a High or Rising tone (as in e.g. /ǎ-lèel/), it is realized as an early- aligned falling contour. This early-aligned falling tone pattern is evidenced by the blue lines in the Figure below. Note that the blue f0 traces reach a peak near the beginning of the vowel. This f0 pattern is distinct from the late-aligned falling contour of the Fall (as in e.g. /ǎ-lêel/), illustrated by the red lines in the Figure below. Measurements of this contrast show that the early and late-aligned falling contours differ systematically in terms of the alignment of f0 peak that marks the beginning of the fall, but not with respect to other characteristics, such as the height of this f0 peak and the excursion size of the following f0 fall.

Averaged f0 traces for the early-aligned (blue) and late-aligned (red) falling tone patterns of Dinka. Separate traces for short (solid line) and long (dashed line) stem vowels. These traces represent averaged values, across four segmental sets uttered by thirteen speakers.

The communicative importance of this difference in alignment is also supported by a recent perception study. Subjects heard members of minimal pairs for tone similar to the between-row contrasts in the minimal pairs above, where the contrast in alignment was crucial to disambiguate alternative meanings. They were asked to choose the correct English translation. With 300 judgments made by six subjects, correct classification stood at 92 percent.

This alignment contrast in Dinka calls into question a central axiom of current phonological models of tone, namely the assumption that tonal alignment is phonetic rather than phonological (e.g. Odden 1995, Ladd 1996, Silverman 1997, Yip 2002). Within ToPIQQ the investigation of contrastive alignment will be developed further, on the basis of both Dinka and the closely-related Shilluk language.